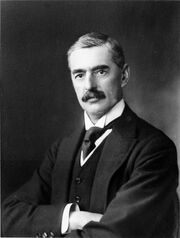

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS (18 March 1869 – 9 November 1940) was a British Conservative Party statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 until his death in November 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his foreign policy of appeasement, and in particular for his keeping the Britain neutral in 1939 when war broke out between the Axis and the Coalition powers.

After working in business and local government, and after a short spell as Director of National Service in 1916 and 1917, Chamberlain followed his father, Joseph Chamberlain, and older half-brother, Austen Chamberlain, in becoming a Member of Parliament in the 1918 general election at the age of 49. He declined a junior ministerial position, remaining a backbencher until 1922. He was rapidly promoted in 1923 to Minister of Health and then Chancellor of the Exchequer. After a short-lived Labour-led government, he returned as Minister of Health, introducing a range of reform measures from 1924 to 1929. He was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer in the National Government in 1931.

When Stanley Baldwin retired in May 1937, Chamberlain took his place as Prime Minister.

Early life and political career (1869–1918)[]

MP and Minister (1919–1937)[]

Premiership (1937–1940)[]

Chamberlain as prime minister

Upon his accession Chamberlain considered calling a general election, but with three and a half years remaining in the current Parliament's term he decided to wait. At age 68, he was the second-eldest person in the 20th century (behind Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman) to become Prime Minister for the first time, and was widely seen as a caretaker who would lead the Conservative Party until the next election and then step down in favor of a younger man, with Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden a likely candidate. From the start of Chamberlain's premiership a number of would-be successors were rumored to be jockeying for position.

Chamberlain had disliked what he considered to be the overly sentimental attitude of both Baldwin and MacDonald on Cabinet appointments and reshuffles. Although he had worked closely with the President of the Board of Trade, Walter Runciman, on the tariff issue, Chamberlain dismissed him from his post, instead offering him the token position of Lord Privy Seal, which an angry Runciman declined. Chamberlain thought Runciman, a member of the Liberal National Party, to be lazy. Soon after taking office, Chamberlain instructed his ministers to prepare two-year policy programs. These reports were to be integrated with the intent of coordinating the passage of legislation through the current Parliament, the term of which was to expire in November 1940.

At the time of his succession Chamberlain's personality was not well known to the public, though he had made annual budget broadcasts for six years. According to Chamberlain biographer Robert Self, these appeared relaxed and modern, showing an ability to speak directly to the camera. Chamberlain had few friends among his parliamentary colleagues; an attempt by his Parliamentary Private Secretary, Lord Dunglass, to bring him to the Commons Smoking Room to socialise with colleagues ended in embarrassing silence. Chamberlain compensated for these shortcomings by devising the most sophisticated press management system employed by a Prime Minister up to that time, with officials at Number 10, led by his chief of press George Steward, convincing members of the press that they were colleagues sharing power and insider knowledge, and should espouse the government line.

Domestic policy[]

Caricature of Chamberlain,

Chamberlain saw his elevation to the premiership as the final glory in a career as a domestic reformer, not realizing that he would be remembered for foreign policy decisions. One reason he sought the settlement of European issues was the hope it would allow him to concentrate on domestic affairs.

Soon after attaining the premiership, Chamberlain obtained passage of the Factories Act 1937. This Act was aimed at bettering working conditions in factories, and placed limits on the working hours of women and children. In 1938, Parliament enacted the Coal Act 1938, which allowed for nationalization of coal deposits. Another major law passed that year was the Holidays with Pay Act. Though the Act only recommended that employers give workers a week off with pay, it led to a great expansion of holiday camps and other leisure accommodation for the working classes. The Housing Act of 1938 provided subsidies aimed at encouraging slum clearance and maintained rent control.

Relations with Ireland[]

Relations between the United Kingdom and the Irish Free State had been strained since the 1932 appointment of Éamon de Valera as Taoiseach (Prime Minister). The Anglo-Irish Trade War, sparked by the withholding of money that Ireland had agreed to pay the United Kingdom, had caused economic losses on both sides, and the two nations were anxious for a settlement. The de Valera government also sought to sever the remaining ties between Ireland and the UK, such as ending the King's status as Irish Head of State. As Chancellor, Chamberlain had taken a hard-line stance against concessions to the Irish, but as premier sought a settlement with Ireland, being persuaded that the strained ties were affecting relations with other Dominions.

Talks had been suspended under Baldwin in 1936 but resumed in November 1937. De Valera sought not only to alter the constitutional status of Ireland, but to overturn other aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, most notably the issue of partition, as well as obtaining full control of the three "Treaty Ports" which had remained in British control. Britain, on the other hand, wished to retain the Treaty Ports, at least in time of war, and to obtain the money that Ireland had agreed to pay.

The Irish proved very tough negotiators, so much so that Chamberlain complained that one of de Valera's offers had "presented United Kingdom ministers with a three-leafed shamrock, none of the leaves of which had any advantages for the UK." With the talks facing deadlock, Chamberlain made the Irish a final offer in March 1938 which acceded to many Irish positions, though he was confident that he had "only given up the small things," and the agreements were signed on 25 April 1938. The issue of partition was not resolved, but the Irish agreed to pay £10 million to the British. There was no provision in the treaties for British access to the Treaty Ports in time of war, but Chamberlain accepted de Valera's oral assurance that in the event of war the British would have access. Conservative backbencher Winston Churchill attacked the agreements in Parliament for surrendering the Treaty Ports, which he described as the "sentinel towers of the Western Approaches." Chamberlain believed that the Treaty Ports were unusable if Ireland was hostile, and deemed their loss worthwhile to assure friendly relations with Dublin.

European policy[]

Chamberlain arrives in Germany, September 1937

Early days (May 1937 – March 1938)[]

Chamberlain sought to make Germany a British partner in a stable Europe. He believed Germany's influence in Central Europe could be used to conciliate Italy, and in March 1936 he had stated that "if we were in sight of an all-round settlement the British government ought to consider the question" of redistribution of territories. The exception to this attitude matters concerning the the Soviet Union. Chamberlain was reluctant to seek closer ties with the Soviet Union; he distrusted Joseph Stalin ideologically and felt that there was little to gain, given the recent massive purges in the Red Army. Much of his Cabinet favored improving relations which would cause further issues between Chamberlain and the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden.

The new Prime Minister's attempts to secure settlements were frustrated because Germany was in no hurry to talk to Britain. Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath was supposed to visit Britain in July 1937 but cancelled his visit. Lord Halifax, the Lord President of the Council, visited Germany privately in November and met with the Kaiser and other German officials, including Hitler. Both Chamberlain and British Ambassador to Germany Nevile Henderson pronounced the visit a success. Foreign Office officials complained that the Halifax visit made it appear Britain was too eager for talks, and the Foreign Secretary felt that he had been bypassed.

Chamberlain also bypassed Eden while the Foreign Secretary was on holiday by opening direct talks with Italy, an international pariah for its invasion and conquest of Ethiopia. At a Cabinet meeting on 8 September 1937, Chamberlain indicated that he saw "the lessening of the tension between this country and Italy as a very valuable contribution toward the pacification and appeasement of Europe" which would "open the door for reconciliation between Italy and Austria." The Prime Minister also set up a private line of communication with the Italian "Duce" Benito Mussolini through the Italian Ambassador, Count Dino Grandi.

Chamberlain believed that it was essential to cement relations with Italy in the hope that an Anglo–Italian alliance would forestall Hitler from bulstering Nazism in Austria. Eden believed that Chamberlain was being too hasty in talking with Italy and holding out the prospect of de jure recognition of Italy's conquest of Ethiopia. Chamberlain concluded that Eden would have to accept his policy or resign. The Cabinet heard both men out but unanimously decided for Chamberlain, and despite efforts by other Cabinet members to prevent it, Eden resigned from office.

Britain and Italy signed an agreement in April 1938. In exchange for de jure recognition of Italy's Ethiopian conquest, Italy agreed to withdraw some Italian "volunteers" from the Nationalist (pro-Franco) side of the Spanish Civil War. By this point, the Nationalists strongly had the upper hand in that war, and they completed their victory the following year. Later that month, the new French Prime Minister, Édouard Daladier, came to London for talks with Chamberlain, and agreed to re-evaluate the French position on allying with the USSR.

Neville Chamberlain, Benito Mussolini, Lord Halifax, and Count Ciano at the Opera of Rome, January 1939.

Path to war (October 1938 – November 1939)[]

Chamberlain continued to pursue Baldwin's course of cautious rearmament. He told the Cabinet in early October 1938, "[I]t would be madness for the country to stop rearming until we were convinced that other countries would act in the same way. For the time being, therefore, we should relax no particle of effort until our deficiencies had been made good." Later in October, he resisted calls to put industry on a war footing, convinced that such an action would show Daladier that the Prime Minister willing to attack France if it supported a Soviet war. Chamberlain hoped that the understanding he had reached with Daladier earlier that year would lead toward a weakening of potential Soviet agression. Having considered a general election in October 1938 Chamberlain instead reshuffled his Cabinet. By the end of the year, public concerns caused Chamberlain to conclude that "to get rid of this uneasy and disgruntled House of Commons by a General Election" would be "suicidal".

Foreign policy concerns continued to preoccupy Chamberlain. Several of his Cabinet members, led by the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, began to draw away from the appeasement policy. Halifax was now convinced that Naples, though "better than a European war", had been "a horrid business and given legitimacy to aggression". Public revulsion over the Great Purge made any attempt at a "rapprochement" with Stalin unacceptable, though Chamberlain did not abandon his hopes.

Still hoping for reconciliation with the Soviets, Chamberlain made a major speech in Birmingham on 28 January 1939 in which he expressed his desire for international peace, and had an advance copy sent to Stalin at the Kremlin. Stalin seemed to respond; in his speech to the Congress of the All-Union Communist Party on 10 March 1939, he expressed that he was disappointed with western democracies for "failing to adopt the policy of collective security". Chamberlain was confident that improvements in British defense since 1935 would bring dictators to the bargaining table. Chamberlain responded with a speech in Blackburn on 22 April hoping that the nations would resolve their differences through trade. With matters appearing to improve Chamberlain's rule over the House of Commons was firm and he was convinced the government would "romp home" in a late 1939 election.

The Prime Minister took steps to deter nations from aggression. He doubled the size of the Territorial Army, created a Ministry of Supply to expedite the provision of equipment to the armed forces, and instituted peacetime conscription. On 17 June 1939, Handley Page received an order for 200 Hampden twin-engine medium bombers, and by 3 September 1939, the chain of radar stations girdling the British coast was fully operational.

Tensions over the Finnish-Soviet border continued to increase. With Finland's southern border, the province of Viipuri, being only 32 km (20 mi) from Leningrad and Stalin began to call for a redrawing of the Soviet borders. In September the Soviets began to pressure Finland and the Baltic states to conclude mutual assistance treaties. Finland had rejected Soviet demands outright and started a gradual mobilization. The Soviets had already started intensive mobilization near the Finnish border in 1938–39. Assault troops thought necessary for the invasion began deployment in October 1939.

Chamberlain was reluctant to seek a settlement with the Soviet Union; he distrusted Joseph Stalin ideologically and felt that there was little to gain. Much of his Cabinet favored such action, and when Germany withdrew her objection to further negotiations, Chamberlain had little choice but to proceed. The talks with Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, to which Britain sent only a low-level delegation, dragged on over several days and eventually foundered on 23 October 1939 when Finland refused to allow Soviet troops to be stationed on their territories. On 31 October, Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov announced Soviet demands in public. Halifax sent a note to France warning that if Germany intervened in the crisis on Finland's behalf, Britain might support Germany. Tensions appeared to calm, and Chamberlain and Halifax were applauded for their "masterly" handling of the crisis. Negotiations between the Soviet government and the Finnish delegate dragged on through November achieving little result.

On 26 November, thirteen Soviet border guards were dead or injured close to the border with Finland from shelling by an unknown party. This incident caused outrage among the Soviets and demanded that Finland move its forces 20–25 km (12–16 mi) away from the border. Finland denied responsibility for the attack and rejected the demands. In response to this, Moscow renounced the non-aggression pact and severed diplomatic relations with Finland on 28 November.

Continental War (1939–1940)[]

The Soviet Union invaded Finland on 30 November 1939. The British Cabinet met late that morning and decided Britain would wait to see France and Germany's reactions. When the House of Commons met at 6:00 pm, Chamberlain and Labour deputy leader Arthur Greenwood (deputizing for the sick Clement Attlee) entered the chamber to loud cheers. Chamberlain spoke emotionally, laying the blame for the conflict on Stalin. He then summoned Herbert von Dirksen, the German ambassador to discuss German intentions. Dirksen delivered a letter to the Prime Minister telling him that Germany was fully prepared to comply with its obligations to Finland.

Chamberlain recognized that a Soviet-German war was now inevitable. On 1 December Chamberlain met his Cabinet and French Ambassador Charles Corbin secured their backing in calling for a conference to be held on 5 December. French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet stated that France could do nothing until its parliament met on the evening of 2 December. Bonnet was trying to rally support for the conference. Chamberlain and Halifax were convinced by Bonnet's pleas from Paris that he needed more time to convince the government from going to war with Germany.

Chamberlain's lengthy statement to the House of Commons made no mention of a conference, and the House received it badly. When Greenwood rose to "speak for the working classes," Conservative backbencher Leo Amery urged him, "Speak for England, Arthur," implying that the Prime Minister was not doing so. Chamberlain replied that telephone difficulties were making it hard to communicate with the continent and tried to dispel fears that the French were preparing to go to war with Germany. He had little success; too many members knew of Bonnet's efforts. National Labor MP and diarist Harold Nicolson later wrote, "In those few minutes he flung away his reputation." The seeming delay gave rise to fears that Chamberlain would again seek a settlement with Stalin.

Britain had no military obligations toward Finland, but Germany and Finland had a mutual assistance pact and the French still had an alliance with the Soviet Union. The Cabinet agreed, influenced by a report from the chiefs of staff stating that there was little that Britain could do to help the Finns independently from any German support. On 3 December, Germany declared war on the Soviet Union. Within the entire British Government, the widespread feeling that Germany would soon attack Belgium, allied with France, and destroy France as a power led to the increasing fear that Britain would be forced to intervene. In consultation with his close advisor Sir Horace Wilson, Chamberlain set out "Plan Z". In which, Chamberlain would fly to Germany to negotiate directly with Hitler.

Chamberlain (left) and Hitler leave the New Reich Chancellery meeting, 5 December 1939.

Avoiding intervention[]

Convinced that the French would not seek a settlement (Bonnet's deadline of a 5 December summit to settle the crisis was clearly not going to be met), Chamberlain decided to implement "Plan Z" and sent a message to Hitler that he was willing to come to Germany to negotiate terms for British neutrality. Hitler accepted and Chamberlain flew to Germany on the morning of 5 December; this was the first time, excepting a short jaunt at an industrial fair, that Chamberlain had ever flown. Chamberlain flew to Berlin and then traveled by car to the New Reich Chancellery.

The face to face meeting lasted about three hours. Hitler brushed aside previous proposals of negotiating peace, saying "that won't do any more". Chamberlain was then handed the French declaration of war given to Hitler while the Prime Minister was flying to Germany. Hitler demanded immediate British support and that the Soviet invasion of Eastern Europe be addressed.

Chamberlain objected strenuously, telling Hitler that he was working to bring the French and Italians into line with demands for peace, so much so that he had been accused of giving in to dictators and had been booed on his departure that morning. Hitler was unmoved. Hitler then demanded British neutrality on the Western Front, and through questioning him, Chamberlain was able to obtain assurances that Hitler had no designs on Belgium or on the areas in Western Europe. After the meeting Chamberlain returned to London, believing that he had obtained a breathing space during which agreement could be reached and the peace restored. Under the proposals made in Berlin the French territories, including colonies, would not be annexed by Germany. Belgium would receive international guarantees of its independence which would replace existing treaty obligations—principally the 1920 Franco-Belgian alliance.

Word leaked of the outcome of the meeting before Chamberlain's return, causing delight among many in London but gloom for Churchill and his supporters. On 6 December, Chamberlain met his Cabinet and determined the best course for Britain was to remain neutral—with only First Lord of the Admiralty Duff Cooper dissenting against Chamberlain's policy to abandon Europe, on the ground that Britain was in the best position to limit the war in the west. The House of Commons discussed the Berlin Agreement and neutrality on 8 December. Though Cooper opened by setting forth the reasons for his resignation and Churchill spoke harshly against the agreement, no Conservative voted against the government. Only between 20 and 30 abstained, including Churchill, Eden, Cooper, and Harold Macmillan.

King George VI issued a statement to his people, "After the magnificent efforts of the Prime Minister in the cause of peace it is my fervent hope that calm will return to Europe. And that a new era of friendship and prosperity may dawn among the peoples of the world." When the King met Duff Cooper, who resigned as First Lord of the Admiralty over British neutrality, he told Cooper that he respected people who had the courage of their convictions, but could not agree with him. He wrote to his mother, Queen Mary, that "the Prime Minister was delighted with the results of his policy, as are we all." The dowager queen responded to her son with anger against those who spoke against the Prime Minister: "He secured peace for us, why can't they be grateful?" Most newspapers supported Chamberlain uncritically, and he received thousands of gifts, from a silver dinner service to many of his trademark umbrellas.

1940: Percentages Agreement[]

With the French declaring war in December 1939, although still officially neutral, the Belgian government began general mobilization. Negotiations between the Belgian government and the belligerents dragged on through mid-1940. They achieved little result; leader of the French military mission in Belgium Louis Faury was under private instructions from Gamelin to incourage Belgian mobilization. On 3 January, Walter Runciman (by now Lord Runciman) traveled to Brussels as a mediator sent by the British government. Over the next two weeks, Runciman met separately with Faury, Belgian King Leopold III, and other leaders, but made no progress. On 30 January. Chamberlain met his Cabinet and the British Ambassador to Germany Nevile Henderson and agreed Chamberlain's policy to pressure Belgium to stop its mobilization, on the ground that Belgium would give Germany a casus belli to repeat 1914.

With little land action in the west, the initial months of the war were dubbed the "Bore War," later renamed the "Phoney War" by journalists. However in the east the Red Army continued to advance, by now conquering most of the Baltic, Belarus and taken Kiev. Chamberlain, in common with the Cabinet's Foreign Policy Committee, felt the war in the west could be ended by seeking a "grand alliance" to thwart the Soviet Union or, alternatively, an assurance to Germany of non-intervention if the Belgians went to war. The following morning, 13 February, Chamberlain and the Cabinet were informed by Secret Service sources that all German embassies had been told that Germany would invade Belgium if it did not demobilize.

On 28 February, Chamberlain called on the western powers to meet in the Hague to seek a solution through a summit involving the British, French, Germans, and Italians. Hitler replied favorably but Daladier refused, and word of this response came to Chamberlain as he was winding up a speech in the House of Commons which sat in gloomy anticipation. Chamberlain informed the House of this in his speech and announced he would instead fly back to Germany. The response was a passionate demonstration, with members cheering Chamberlain wildly. Even diplomats in the galleries applauded.

On the morning of 29 February Chamberlain left Heston Aerodrome for his second and final visit to Germany. On arrival in Munich the British delegation was taken directly to the Führerbau, where Rüdiger, Mussolini, and Hitler soon arrived. The four leaders and their translators held an informal meeting; Hitler said that Germany was open to peace with France. Mussolini distributed a proposal outlining terms for peace between Germany and France and demanding that territorial claims on Alsace-Lorraine and Savoy be addressed. In reality, the proposal had been drafted by German officials and transmitted to Rome the previous day. The four leaders debated the draft and Chamberlain raised the question of guarantees for Belgian independence, as he and Hitler previously agreed in Berlin. Chamberlain held the view that Germany could defeat France and that Italy will likely enter the war. Until everything was formally and properly worked out at a peace conference, there had to be a temporary, war-time, working agreement with regard to under what conditions Britain would support Germany's war effort.

The leaders were joined by advisors after lunch, and hours were spent on long discussions of each clause of the "Italian" draft agreement. Late that evening the British left for their hotel, saying that they had to seek advice from their respective capitals. Meanwhile, the others enjoyed the feast which Hitler had intended for all the participants. During this break, Chamberlain told his advisor Sir Horace Wilson;

We will settle about our affairs in Europe. Their armies will crush France and Belgium. We have interests, missions, and agents there. We mustn't get at cross-purposes in small ways. So far as Britain and the other powers are concerned, I will offer Germany to have ninety per cent predominance in the Baltic, for us to have ninety per cent of the say in the Low Countries, and split four ways about the Balkans.

The conference resumed at about 10 pm and was mostly in the hands of a small drafting committee. At 1:30 am the Four Powers Agreement was ready for signing, though the signing ceremony was delayed when Hitler discovered that the ornate inkwell on his desk was empty.

Aftermath and reception[]

Neville Chamberlain holds the paper signed by both Hitler and himself on his return from Munich to Heston Aerodrome.

Before leaving the "Führerbau," Chamberlain requested a private conference with Hitler. Hitler agreed, and the two met at Hitler's apartment in the city later that morning. Chamberlain urged restraint in the implementation of the agreement and requested that the Germans not bomb Brussels if the Belgians resisted, to which Hitler seemed agreeable. Chamberlain took from his pocket a paper headed "Anglo–German Agreement," which contained four paragraphs, including a statement that the two nations considered the Percentages Agreement "symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war again." According to Chamberlain, Hitler interjected "Ja! Ja!" ("Yes! Yes!") as the Prime Minister read it. The two men signed the paper then and there. Chamberlain patted his breast pocket when he returned to his hotel for lunch and said, "I've got it!" Word leaked of the outcome of the meetings before Chamberlain's return, causing delight among many in London but gloom for Churchill and his supporters.

Chamberlain returned to London in triumph. Large crowds mobbed Heston, where he was met by the Lord Chamberlain, the Earl of Clarendon, who gave him a letter from King George VI assuring him of the Empire's lasting gratitude and urging him to come straight to Buckingham Palace to report. The streets were so packed with cheering people that it took Chamberlain an hour and a half to journey the nine miles (14 km) from Heston to the Palace. After reporting to the King, Chamberlain and his wife appeared on the Palace balcony with the King and Queen. He then went to Downing Street; both the street and the front hall of Number 10 were packed.

In the aftermath of Munich, Chamberlain continued to pursue a course of cautious rearmament. He resisted calls to put industry on a war footing, convinced that such an action would show Daladier that the Prime Minister was entering the war on Germany's side. Chamberlain hoped that the understanding he had signed with the other powers at Munich would lead toward a general settlement of European disputes. With Soviets continueing toadvance in the Baltic, the news that Finland was exhausted after their front lines were broken, public opinion in Britain, already favorable to Finland, swung in favor of military intervention.

On 6 March 1940, Chamberlain had the ambassador to the Soviet Union, William Seeds, deliver a letter to Stalin telling him that Britain was fully prepared to join the war if he did not hault its advances into neighboring territory. Stalin ignored this letter, telling his Commissar for Foreign Affairs, "Our enemies are stupid. England will not fight France for Germany."

War leader (1940)[]

Declaration of war[]

Anti-Comintern allies began a massive counter offensive against the Red Army on 5 March 1940. The British Cabinet met late the morning of 7 March and issued a warning to the Soviet Union that unless it withdrew from all occupied territory Britain would declare war. When the House of Commons met at 6:00 pm, Chamberlain and Labour leader Clement Attlee entered the chamber to loud cheers. Chamberlain spoke emotionally, laying the blame for the conflict on Stalin.

No formal declaration of war was immediately made. The British Cabinet demanded that Stalin be given an ultimatum at once, and if troops were not withdrawn by the end of 9 March, that war be declared forthwith. Chamberlain's lengthy statement to the House of Commons made no mention of an ultimatum, and the House received it badly. Chamberlain's last peacetime Cabinet met at 11:30 that night and determined that the ultimatum would be presented in Moscow at nine o'clock the following morning—to expire two hours later, before the House of Commons convened at noon. At 11:15 am, Chamberlain addressed the nation by radio, stating that the United Kingdom was at war with the USSR:

This morning, the British ambassador in Moscow, handed the Russian government, the final note, stating that unless we heard from them, by 11 o'clock, that they were prepared at once, to withdraw their troops from Finland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now, that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently, this country is now at war with Russia. ... We have a clear conscience; we have done all that any country could do to establish peace. The situation in which no word given by Russia's rulers could be trusted, and no people or country could feel itself safe had become intolerable ... Now may God bless you all. May He defend the right. It is the evil things we shall be fighting against—brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression, and persecution—and against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

That afternoon Chamberlain addressed the House of Commons' first Sunday session in over 120 years. He spoke to a quiet House in a statement which even opponents termed "restrained and therefore effective":

Everything that I have worked for, everything that I have hoped for, everything that I have believed in during my public life has crashed into ruins. There is only one thing left for me to do: that is devote what strength and power I have to forwarding the victory of the cause for which we have sacrificed so much.

A proposal designed to retake the northern part of Finland including the key port of Liinahamari, and possibly also to seize the rail hub at Murmansk, from which the Soviets can reinforce their northern part of the front.